A Brief History

An introduction to the history of Berkhamsted Castle

Early Days

© Alderney Bayeux Tapestry Finale 2013

The story of Berkhamsted Castle begins with Duke William of Normandy. After the defeat of Harold at the Battle of Hastings on 14th October 1066, William marched with his army through southern England, pillaging as he went. Crossing the Thames at Wallingford, he reached Berkhamsted.

Here he was met by Archbishop Ealdred, the Bishops of Worcester and Hereford, Earls Eadwin and Morcar, and the chief men of London, who swore allegiance to him, and offered him the crown.

William proceeded to London where he was crowned king on Christmas Day 1066.

William granted the Manor and Honour of Berkhamsted to his half-brother Robert, Count of Mortain. Berkhamsted was of strategic importance, since there was already a Saxon fort guarding the main route north through the valley.

Construction

Robert of Mortain set about building a strongly fortified castle, a typical Norman motte and bailey castle with a tower or keep built on an earthen mound surrounded by a defensive enclosure. The castle was constructed at the bottom of a dry valley where there were springs to fill the moats. The first castle was a timber structure.

Becket's rebuilding

© Harry Sheldon 1999

When William, Robert of Mortain’s son, rebelled against the king, his father’s castle was destroyed. Henry I’s chancellor Randulph then erected a new wooden castle and carried out extensive restoration.

It was when Thomas Becket became Lord Chancellor in 1155 that most money was spent on the buildings and it is to this time that the earliest stone buildings date. In 1157-8 £10 was spent on the king’s houses on the motte and 40s building a chamber within the bailey. In the following year £14 was spent on ‘the work of the chamber and the motte’. Building work continued and was extensive. The ‘chamber of St. Thomas’ was constructed and also houses in the round keep.

King John

With dreams of regaining Normandy, King John had imposed some unpopular taxes for his military expeditions against Philip Augustus of France. This included demanding enormous fees for a baronial heir to inherit property. His relationship with his barons thus already strained, the King infuriated them further by choosing a foreigner, Peter des Roches the Bishop of Winchester, to take over while he was away.

On his return in 1214, there were still barons who were willing to negotiate, but there were also rebels who would eventually rise against the King.

The Magna Carta of political and civil liberties (which outlawed some of the King’s methods of taxation) was drawn up. To buy some time, the King signed it at Runnymede in 1215. However, John had no intention of allowing Magna Carta to stand and wrote immediately to the Pope to have the charter annulled.

This sparked a civil war and the barons invited Prince Louis of France to become king of England. The French prince landed and marched on London. King John was forced to retreat. He fell ill and died in Oct 1216, leaving his nine year old son Henry III as king.

Besieged!

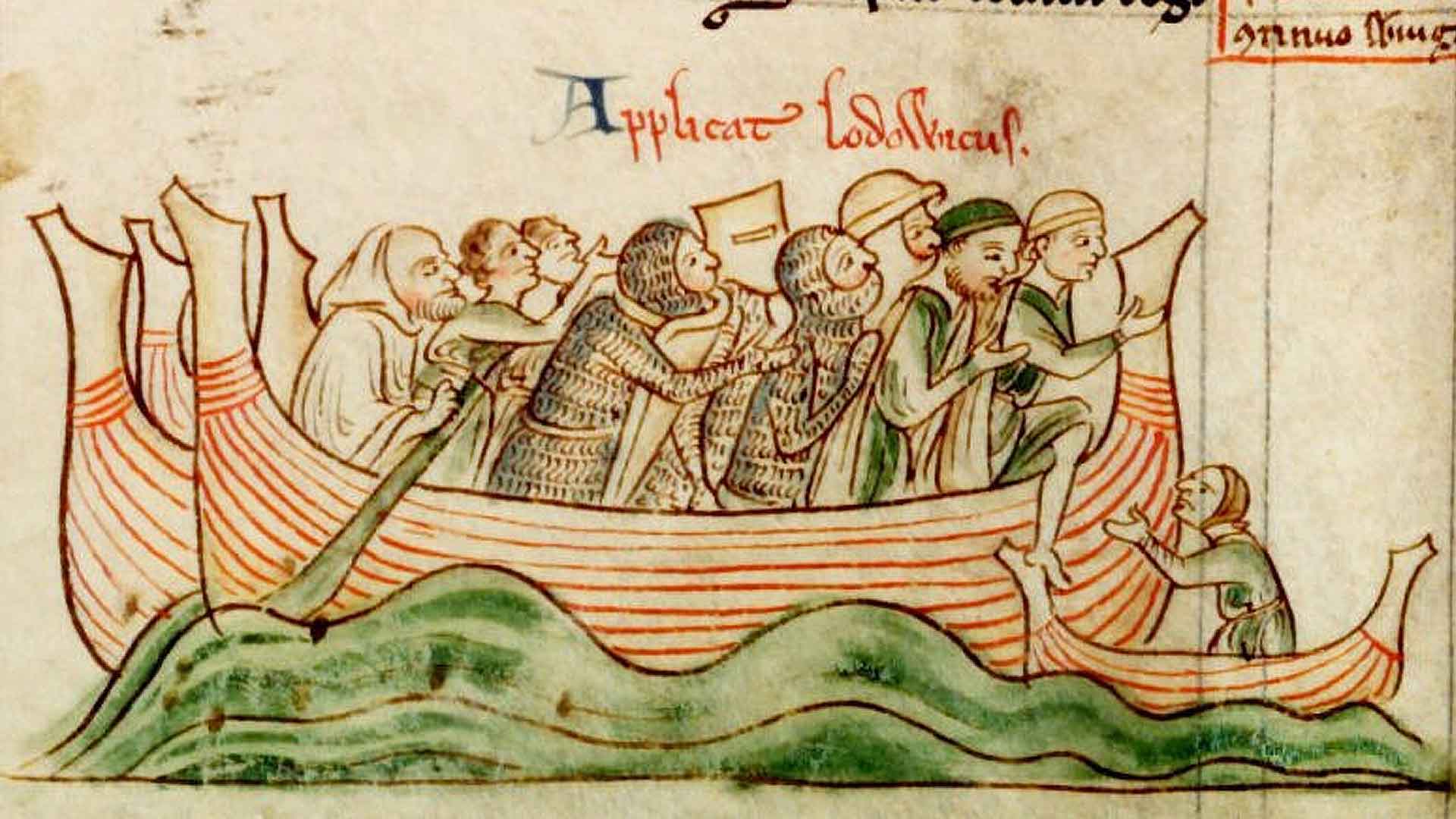

Public Domain image/British Library

In December 1216, Berkhamsted Castle was besieged by Prince Louis of France.

Maybe the attackers halted in their march to wonder at the double-moated fortress that was their target. Beyond the counterscarp bank to the North and East at Berkhamsted Castle was a further bank backed by seven earth bastions. It is said that these were built by the attacking forces, but it is more likely that they were part of King John’s earlier restoration efforts.

It is likely that the constable at the castle was aware of the approach of a hostile force of French mercenaries. He will have hastily arranged for plentiful food supplies to be brought in: bread, cheese, eggs and meat. Hopefully, he would have sent women and children out of harm’s way, if only to preserve the food and drink supplies for fighting men. Wells in the bailey and on the motte provided plentiful water and they would have hunkered down, ready for the attack.

It is said that Prince Louis introduced a new and even more terrifying siege engine to England and used it at Berkhamsted—the trebuchet or mangonel. This worked like a catapult, with a large stone being placed in a sling at the end of the long beam. In the early days, people exerted downward pull on the short end of the beam to flip up the longer end. As designs became more sophisticated, a counterweight was used to provide the downward pull. It was by trial and error that the trajectory and distance were worked out. It seems likely that these siege engines were constructed at the site, rather than being transported.

Most siege engines, such as the mangonel, were capable of throwing a stone of 300 lbs or more a distance of at least 150 metres. The effect would have been devastating on the walls and towers of the castle and terrifying for those cowering within.

Waleran, a German mercenary soldier had supervised the strengthening of the defences, but put to the test, they failed.

King Henry III ordered his constable at the castle to surrender after two weeks on humanitarian grounds. Hopefully this was not in response to a common practice in those days of catapulting dead animals into the castle grounds in the hope of spreading disease.

Earls of Cornwall

For most of the thirteenth century the castle was held by the Earls of Cornwall. Richard and his wife Isabella, who spent much time at Berkhamsted, built a chapel and made great improvements to the hall and the lord’s quarters. When Isabella died, Richard married Sanchia de Provence and their son Edmund was born at the castle in 1249.

In 1254 a tower was built and later repairs were made to the barbican, keep and a turret over the sally port. Work was also carried out on the residential parts – the King’s and Queen’s chambers, the Queen’s chapel, the nurse’s chamber.

Edward III

Edward III was often at Berkhamsted, when his brother held the castle, and in his time costly repairs were made. The great tower was repaired and re-roofed. Restoration work was done on the great painted chamber and the chapel, walls, turrets and outer gate all needed attention. A survey by Edward III in 1337 mentions a ‘great painted chamber and great chapel and also the gate below the said ward, which is called Dernegate, with the gate there of the drawbridge by the moat, and the third bridge that leads towards the park towards the second moat there and the third bridge which leads outwards.’ Repairs estimated at £700 were finished by 1340.

The Black Prince

The castle probably reached its zenith for gaiety and entertaining in the periods when Edward the Black Prince, first Duke of Cornwall was there. When he married Joan, the fair maid of Kent in 1361, their honeymoon was spent in the castle, and the entire court entertained for five days.

Cecily Neville, Duchess of York

Public Domain image/National Portrait Gallery

During the Wars of the Roses the castle changed hands frequently, but times were more placid when the castle came into the hands of Cecily Neville, Duchess of York and granddaughter of John of Gaunt. She led an orderly religious life and her ‘ Rules for the House’ show great care and thought for her tenants. When she died in 1495 the castle was given up as a home.

Cecily died at the Castle in 1495, and that must have been a very black year in local history. The town’s long, intimate link with the Royal Family was snapped. Berkhamsted was without a great house and a great lord or lady. The large domestic staff was disbanded and many a faithful servant must have been unemployed.

Of course, work in the fields and in the park continued. In 1502 the underkeeper at Berkhamsted sent a buck to Windsor for Cecily’s granddaughter, Henry VII’s queen, to whom the Honour and Manor of Berkhamsted was granted. But the first Tudor queen probably never came to Berkhamsted. Neither did Katherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn or Jane Seymour, three of Henry VIII’s wives, to whom the Honour was also granted.

Berkhamsted Place

After the death of Cecily, nearly a century elapsed before Sir Edward Carey built a new mansion, Berkhamsted Place. By that time the Castle was in an advanced state of ruin and the need for defended homes had passed.

The building of Berkhamsted Place pointed to a more peaceful future. It is fitting that into its building went faced stone and flints from the castle, which he held from his queen, Elizabeth I.

A Heap of Stones

Camden, early in the 17th century, saw the damage wrought by Carey’s masons and said the Castle was a heap of stones and ruined walls. A survey of the same period tells us that Carey “hath builded certaine howses fir his necessary use, within the p’cincte of the said Castle.” As we know from the plan [printed in June 1967], a brewhouse, a stable and what seems to have been a lodge had been built in the arena.

In 1728 Salmon described the Castle as “a building with most of the outer walls and chimneys remaining, and all the windows opening to the inside.” Stukeley (1776) agreed that the windows looked inwards and said that the chapel seemed to have stood near the west wall, where there were signs of a staircase.

Even those traces had gone by 1855, when our local historian Cobb wrote: “Windows, chimneys and staircases there are none. Walls there certainly are, but so hopelessly ruinous that the remains do little more than mark their original site.”

Orchard and Pasture

An orchard in the arena, shown in the plan of 1607, survived until the 19th century. In 1811 Dugdale wrote: ‘The inner court is now an orchard; the outer court is cultivated as a farm; and a small cottage with a few outbuildings, now occupies a portion of the ground once occupied by princes and sovereigns.’

Coming of the railways

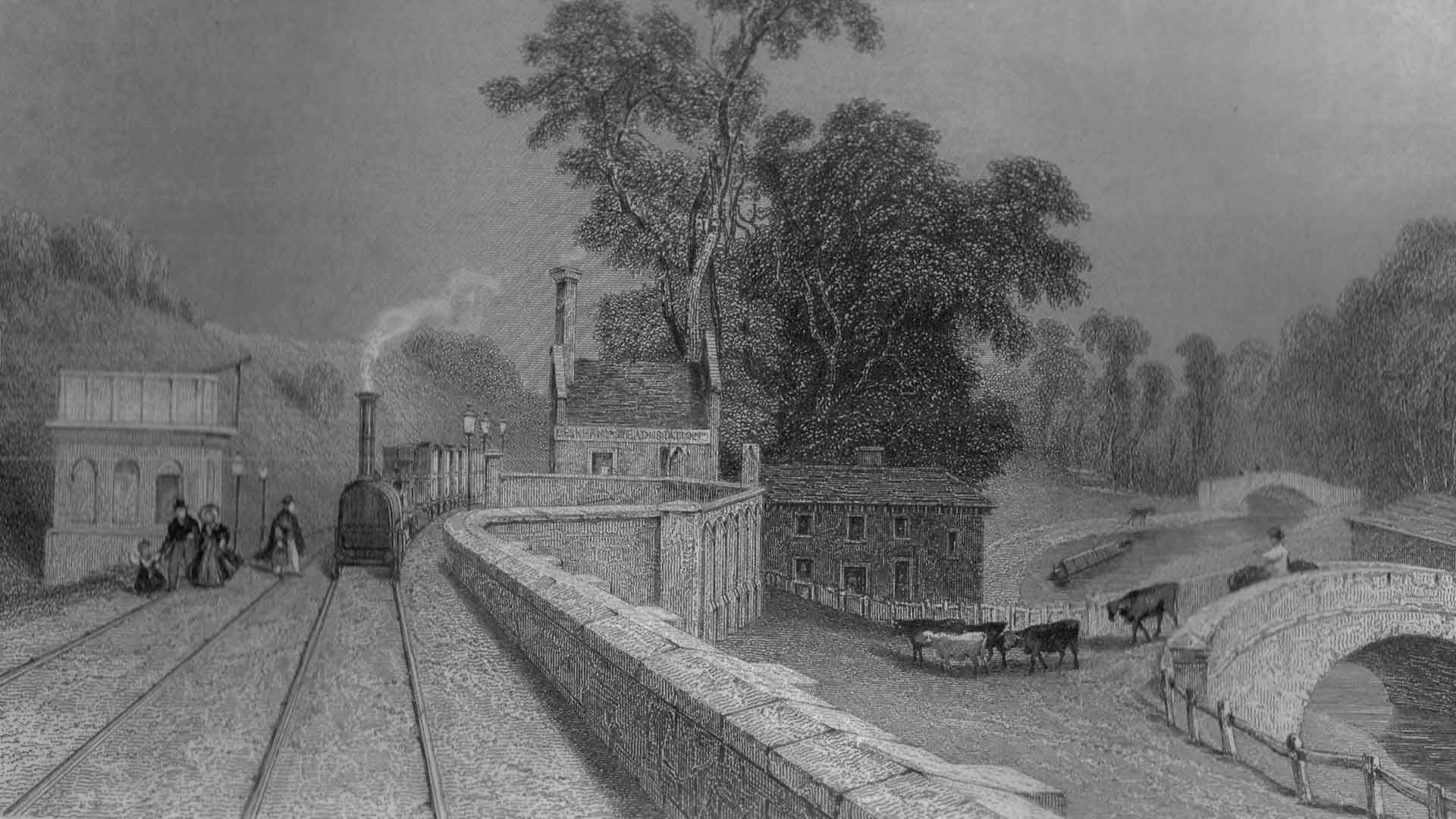

Public Domain image

At the height of the Industrial Revolution, the neglected Castle stood in the way of ambitious railway engineers. When the London and Birmingham Railway built its new line through Berkhamsted in 1837, the ruins of the barbican gate were demolished and the southern outer moat was filled in. What the French trebuchets had failed to destroy in the 13th century had now been eradicated by Victorian navvies.

Conserving an ancient monument

In the 20th century, the cultural value of ancient monuments came to be more widely recognised. Governments moved to protect Britain’s historic assets. Berkhamsted Castle, like hundreds of other ancient sites, was placed under the guardianship of the Office of Works (later the Ministry of Works). Extensive restoration work was undertaken, overgrown trees were felled and the moats were filled with water.

The Castle today

Today, Berkhamsted Castle is under the care of English Heritage (a successor organisation to the Ministry of Works). Since 2018, Berkhamsted Castle Trust has been managing the Berkhamsted Castle site in partnership with English Heritage under a Local Management Agreement.

Parts of this text are taken from:

- ‘Why the Castle was Abandoned’, P.C. Birtchnell, writing as Beorcham in Berkhamsted Review, Jul 1967

An orchard in the arena, shown in the plan of 1607, survived until the 19th century. In 1811 Dugdale wrote: ‘The inner court is now an orchard; the outer court is cultivated as a farm; and a small cottage with a few outbuildings, now occupies a portion of the ground once occupied by princes and sovereigns.’